by Kelly Keene

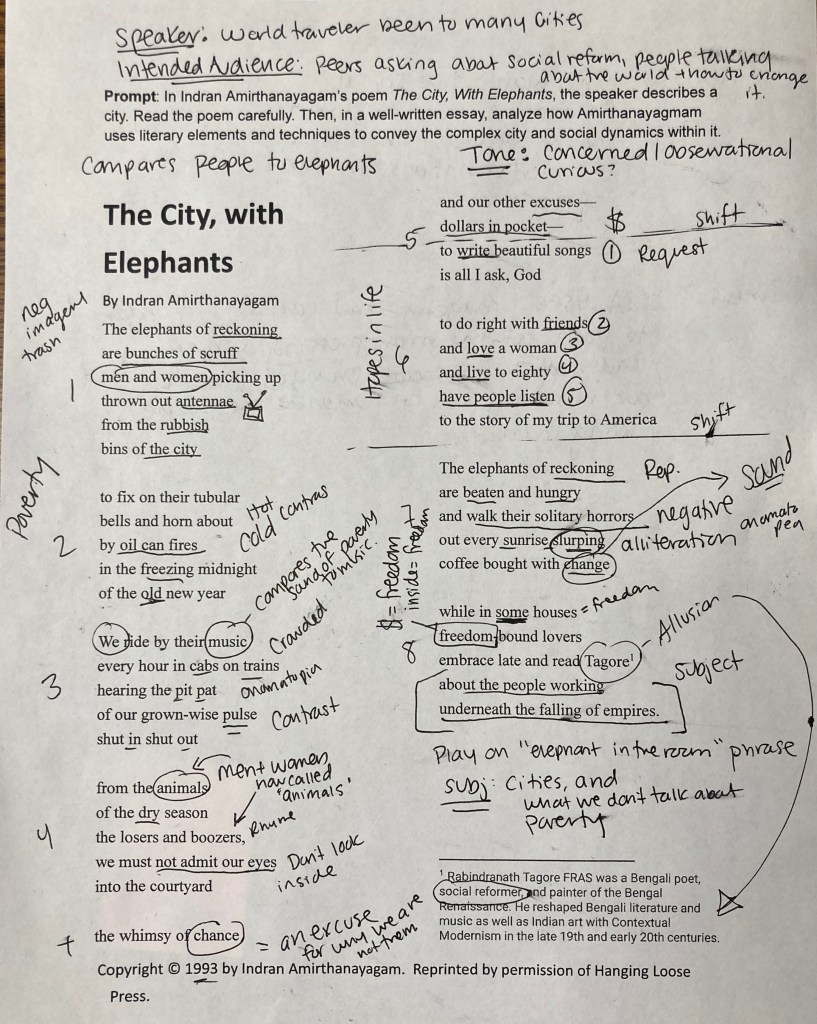

Elephants have incredible memories. They form tight-knit communities, and are even known to mourn their dead, and remember them seasons after they’ve passed. In Indran Amirthanayagam’s poem The City, with Elephants, he uses the image of “the elephants of reckoning” to describe a city with a disconnect between its working and privileged classes. He adopts the voice of a world traveler, who views communities through a wider lens. He recognizes his own vantage point, but also sees the disparity between people who have the luxury to wish for friendship, health, and social progress (stanza 6), and those that wake at “sunrise slurping coffee bought with change” (stanza 7).

His use of the word “change” in stanza seven has two meanings. There is the change in our pockets that we scrounge together to buy that cup of coffee, that gets us through the day. This evokes an image of someone trying to make ends meet, and needing what little they do have to reinvest in the energy it takes to get up and hustle. “Change” can also mean social change. In Stanza eight, the speaker alludes to Tagore, a Bengali poet that writes about social change. The people who might benefit the most from the social change Tagore explores in his poetry, are the ones using any spare change they have to just get by. Those with the time and resources to make life in a crowded urban city better, are wishing, instead, for more time with friends, women to love, and a higher-than-average lifespan (stanza 6).

So who are these elephants? In the beginning of the poem, Amirthanayagam describes them as “bunches of scruff” or “men and women picking up” scraps “from rubbish bins.” The scraps they find are “antennae” (stanza 1). Symbolic receptors that allow these people to understand the signals of their social climate. Their means of grappling with politics and mainstream media, like television, is hindered by their need to scavenge the very means they would need to participate in such conversations. The word “antennae” can also conjure the image of ants on a hill, scavenging for scraps of food.

In the second stanza, Amirthanayagam uses the contrast of hot and cold imagery to point to this paradox of social change. While their means of survival warm them, the “freezing midnight” is oppressive. The oxymoron of an “old new year” highlights how poverty can be a cycle, a never ending trap. Like a wheel going round and round, there is rhythm to a city with rigid social classes. There is a fixed pattern. We see this pattern echoed in Amirthanayagam’s sound devices. It’s in the “pit pat” sounds in stanza three, and the beating “pulse” of the city. This type of rhythm might be comforting to some, but not others. While some are “shut in,” others are “shut out” (stanza 3). When cycles of poverty are fixed, the gap between the privileged class and methodical, symbolic “elephants” widens.

Amirthanayagam does provide a possible reason for this disconnect. In stanza five, we see his tone shift from describing this chasm to offering “other excuses” for why those that do have power don’t do anything about the people they witness struggling from the comfort of their “cabs and trains” (stanza 3). They believe they are lucky. It’s “the whimsy of chance” that gives some opportunities and not others (stanza 5). Or at least that’s what we tell ourselves. We live our lives asking a higher power for more “dollars in our pocket” and the chance to create art (stanza 5). The speaker mocks this way of thinking, and puts it after the image of “loosers and boozers” to show how disconnected and unsympathetic it really is (stanza 4). A city is a place of contrasts. When scores of people live in close proximity, they can see disparity and class divides. The City, with Elephants that Amirthanayagam considers in his poem, is one trapped in a loop, but that doesn’t mean those who feel this disparity most acutely do not remember how it feels.